…The story of rice and Nigeria is more interesting than you think

Nigeria is going through a severe economic crisis that is perhaps the worst in a generation. The currency has broken all psychological barriers against the dollar and food inflation shows no sign of letting up. Things are not quite yet at hyperinflation levels but prices of everything seem to change daily and only head in one direction.

While the crisis might seem sudden, the problems have been long in coming and there are hardly any easy solutions in sight especially when it comes to food supply and prices. Rice – the subject of this post – presents a useful case study.

Data Caveat – You will note that this post uses a combination of USDA and FAO data sources. While both data sources are directionally the same, they have some differences that should be noted. People who know these things much better than I do tell me that the USDA uses more on-the-ground sources to gather their data while the FAO tends to rely on national sources like the Ministry of Agriculture’s surveys. The USDA’s data tends to align more with other sources like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) who both conduct household surveys. Overall, the USDA estimates that Nigeria has higher rice yields and a lower area cultivated while the FAO thinks Nigeria’s yields are lower but with a higher area cultivated (mainly driven by the Anchor Borrowers Programme which pulled in a lot more farmers, many of whom did not know what they were doing. The flip side is that the nature of the program meant people have incentives to report higher numbers). Overall, the sense is that the USDA’s data is more reliable.

MidJourney Prompt: Nigerian farmer discarding cassava in favour of rice with a very happy smile on his face

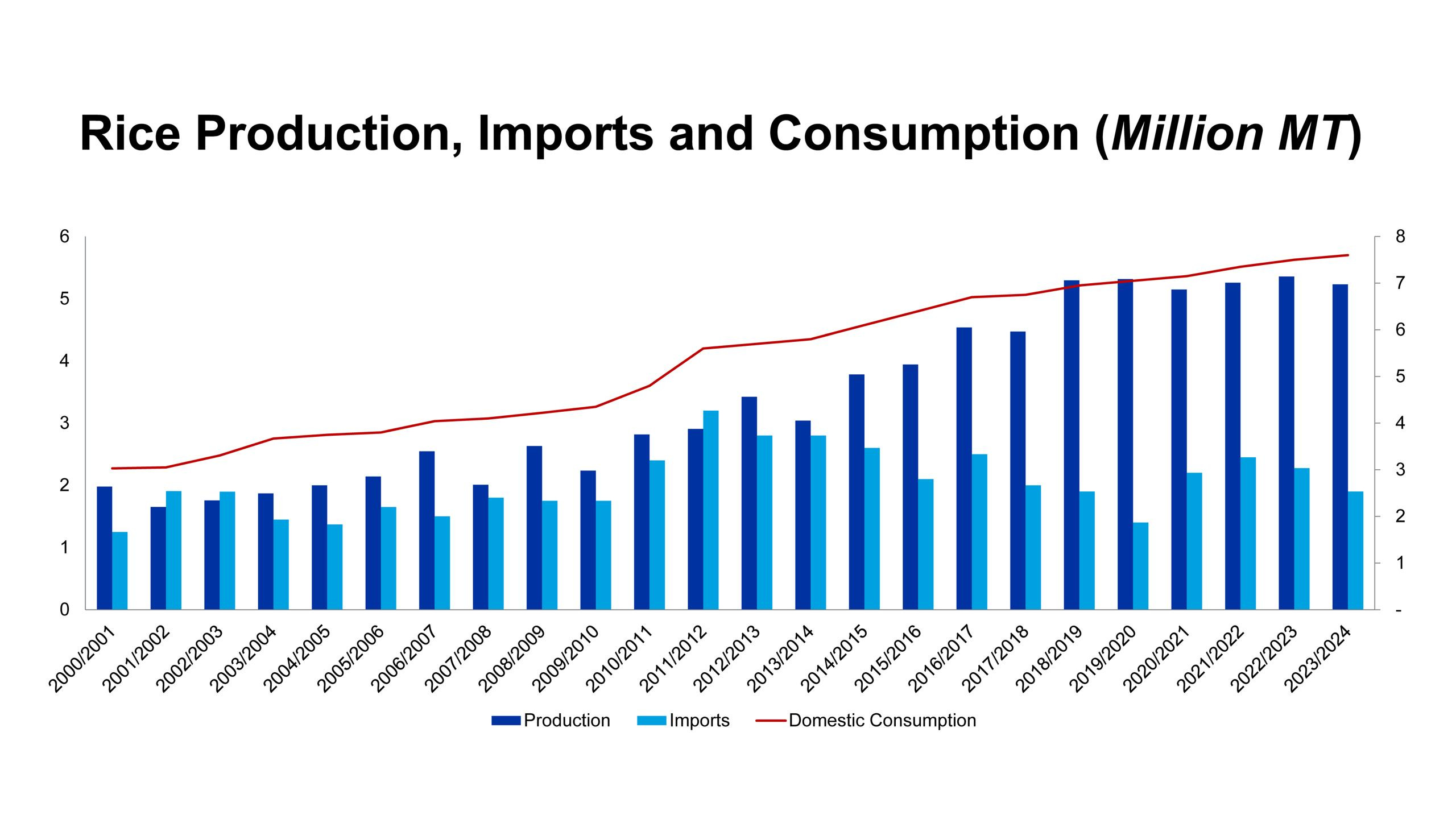

Nigeria is a fairly large consumer of rice as the chart below from the USDA shows:

The numbers are not crazy large but that can be explained by high rates of poverty (many Nigerians would eat more rice if they had more money) and the fact that rice is not part of Nigerian foods in the same way that it is the base food in most Asian countries.

A recent BBC report had this to say on what Nigerians are currently contending with in terms of rice prices:

Prices in Nigeria are increasing at their fastest rate for nearly 30 years. On top of global pressures, President Bola Tinubu’s cancellation of the fuel subsidy plus the devaluation of the currency, the naira, have added to inflation.

A standard 50kg (110lb) bag of rice, which could help feed a household of between eight and 10 for about a month, now costs 77,000 naira ($53; £41). This is an increase of more than 70% since the middle of last year and exceeds the monthly income of a majority of Nigerians.

The reason for this sounds straightforward – the naira has collapsed against the US dollar and since Nigeria imports a lot of prices, paid for in dollars, local prices have correspondingly shot up.

Rice is an untold Nigerian success story

Except that’s not the whole story. Consider the chart below put together by a friend (discussing with him triggered this post) using USDA data:

This is one of those recurring features of a lot of Nigerian production where minority imports set the market price even for local production. On average, over the last couple of decades, Nigeria has needed to import 2 million metric tonnes of rice annually to supplement local production. From the chart, you can see that imports used to make up more than local production a couple of decades ago. In such a scenario, you’d expect prices to shoot up following a collapse in the currency.

But that is not the case here. In just two decades, Nigeria has more than doubled its price production (albeit from a low base) and imports now make up only about 25% of total consumption. Yet the price of everything – locally produced and imported – has shot up in lock step with the dollar. What explains this? The only conclusion is that the tariff protections put in place to boost local production have now exceeded their usefulness and Nigeria has hit the ceiling of what it can reasonably produce locally. As my friend put it, the tariffs remaining in place is “just punishment for ordinary Nigerians now”. Import tariffs on rice in Nigeria go as high as 60% for ‘semi-milled or wholly milled rice, whether polished or glazed’ (broken out into 10% import duties and 50% levy). If you’re tempted to say that farmers’ inputs cost dollars, the import duties on rice seedlings is only 5% (same for paddy rice). In this scenario, local farmers can make a handsome profit by simply pricing according to what the imported rice lands at. In other words, Nigerians are paying the duties and levy on both local and imported rice.

The Rice Production Ceiling

But what is the reason for the assertion that Nigeria has hit its production wall? The first thing to investigate is always yields. How much better are the yields in countries where Nigeria imports a lot of rice from? We will use Thailand as our comparison. But first some caveats – Nigeria does not import much rice from Thailand anymore for a number of reasons. One was the coming of India onto the rice markets as an export force (and much cheaper supplier) in the last decade. Then there’s China whose scale no one can really match. There’s also another point to be made that China and India have much higher rice yields than Thailand so this is not comparing Nigeria to the global best in class.

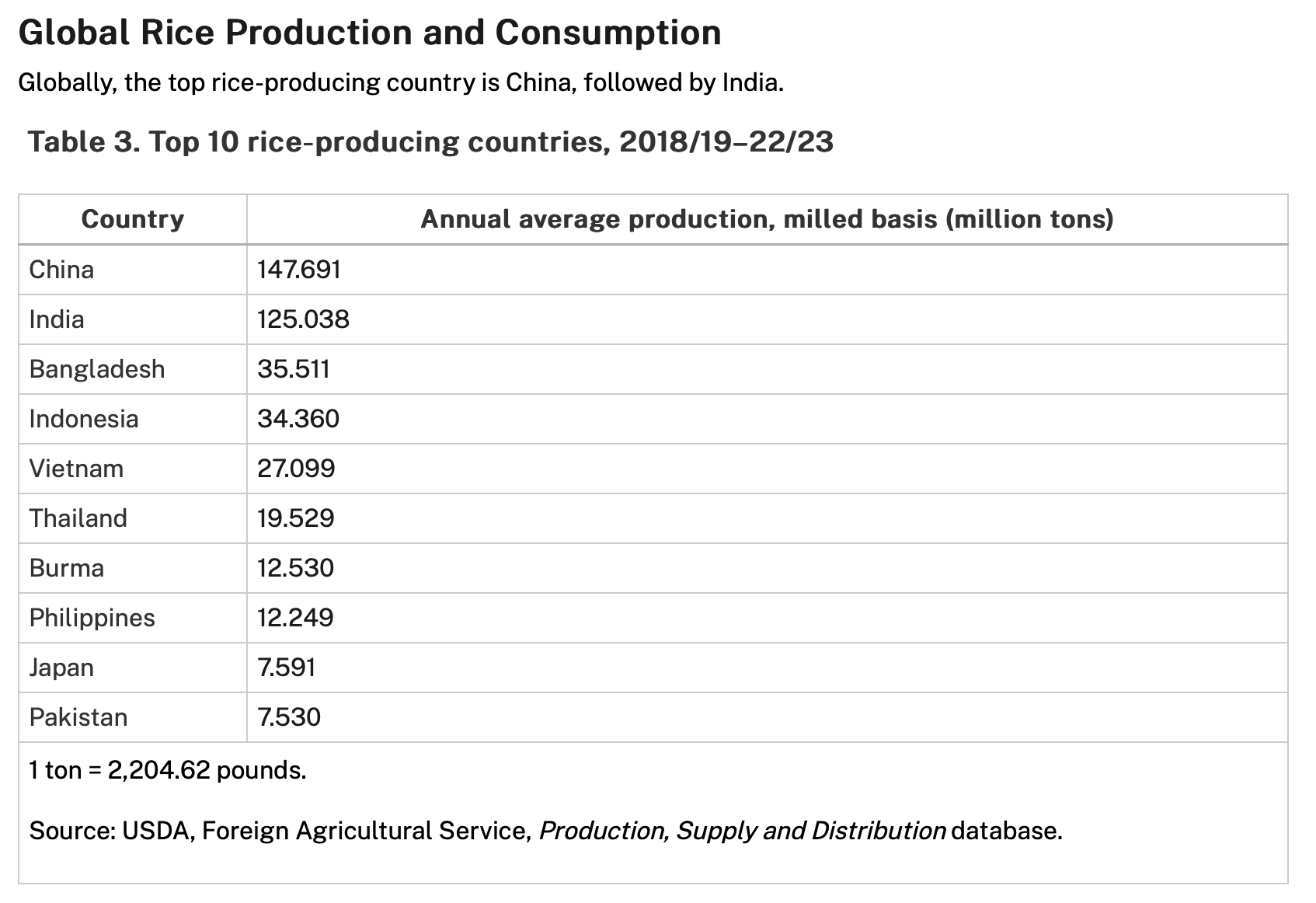

Be that as it may – from the USDA again – here’s what global production currently looks like:

Different sources may give different production numbers but for this exercise, the chart above is sufficient. Thai rice has always carried a mark of quality and for many years it was a favourite of Nigerians.

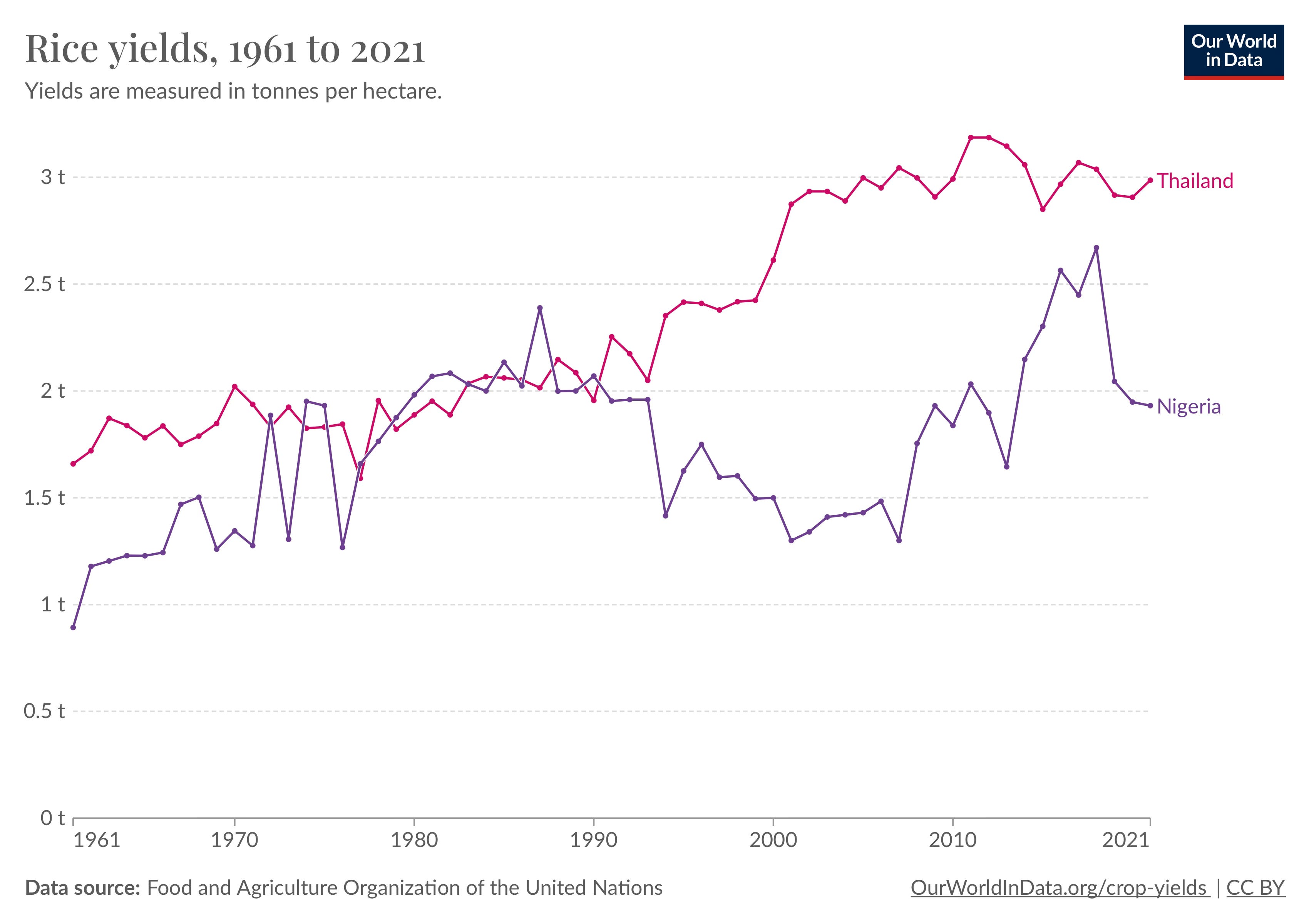

So how much better are rice yields in Thailand compared with Nigeria?

This chart may be surprising to some (it was for me). Very recently, Nigeria had almost caught up with Thai rice yields. I don’t know what has caused the recent divergence but I will put it down to a combination of armed banditry, terrible flooding in recent years and that awful Quelea bird doing untold damage to rice farms across the north.

So yields alone cannot explain why Thailand produces far more rice than Nigeria manages. As we can see from the production and consumption charts above, it should not be too difficult for Nigeria to produce as much rice as it needs and even export some as Burma and Vietnam do.

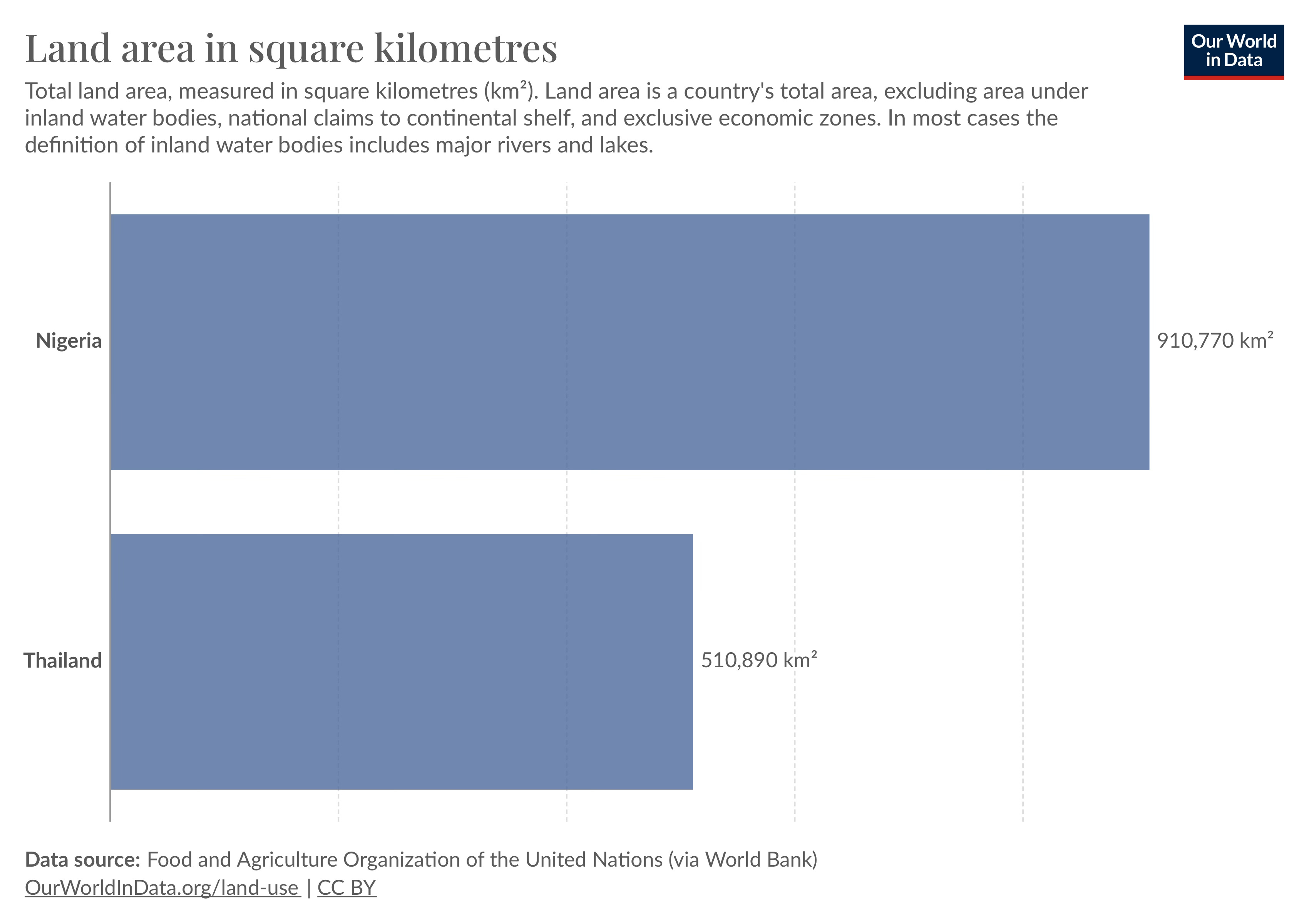

But here’s the money chart:

In summary, Thailand’s much larger production of rice, compared to Nigeria, is explained almost entirely by using far more land for rice farming. This makes sense given that yields are not too far off from Nigeria. So the solution for Nigeria to produce that extra 25% of consumption it needs locally is fairly straightforward – dedicate more land to farming rice. For sure, Nigeria is a much larger country than Thailand, in terms of land area so if Thailand can find 10 million hectares to plant rice, Nigeria can find a few more million hectares to boost rice production.

Variety is a challenge to food security

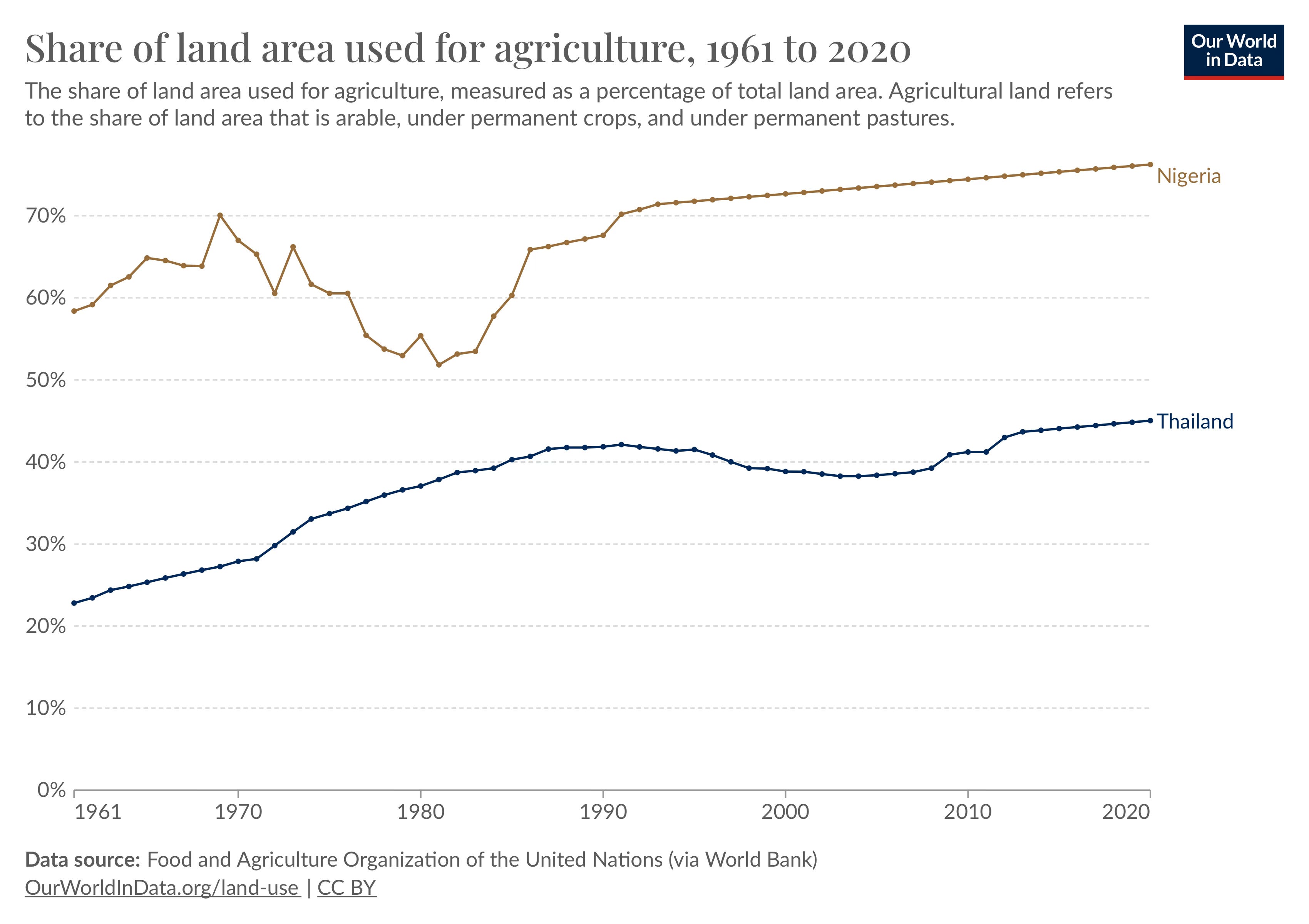

Except that it’s not so straightforward. Here we get into what and how people eat as a nation. Here’s Thailand’s general land use for agriculture:

Rice plays a much bigger role in Thai food security as it’s a base food for so many things. From their point of view, the thing to solve for food security is rice. Once that’s done, the rest is relatively straightforward. And that’s reflected in how much land is used for rice compared with everything else.

Here’s what Nigeria looks like in comparison:

The difference is stark. Just for maize alone, Nigeria uses six times more land than Thailand uses, while for that awful cassava, it is about eight times. Nigerians eat a lot of different foods to the point where you cannot simply target one crop for abundance to solve food security. Nigerians eat a lot yams, they eat a lot of maize, they eat a lot of rice, they eat a lot of cassava. Here’s another way to look at it:

Nigeria already uses more than 70% of its land area for agriculture compared with less than 50% in Thailand. There is not a lot of room left to go given Nigeria’s increasing population and urbanisation trends.

And this brings us back to the earlier point about Nigeria hitting its rice production ceiling. There is already so much going on with Nigerian food that there is very little room to manoeuvre without making trade-offs. To grow more rice, Nigeria will probably need to grow less of something else.

For a crop that does not really belong to Nigeria, the country has done remarkably well with rice production. The government used policies to get Nigerian farmers to produce more rice and they responded quite well to the incentives. These policies also had the effect of increasing the salience of rice among Nigerians to the point where Nigerians now eat more rice than they normally would without any government intervention. If the government can get Nigerians to eat more of something, it stands to reason it can also get them to eat less of something else, too.

If there is a painful choice to be made in terms of what to give up to have more rice, then it is with a heavy heart that I must put forward Cassava. The less of this crop that Nigeria grows, the better for the whole world.